Contemporary Conspiracy Theories: Contextual Factors

Dec 1, 2020 —

In this post, we want to provide some macro context that will be useful for understanding the place, role, and tenor of conspiracy theories during the pandemic. We want to situate the current crisis and its attendant “infodemic” within other, slower crises that concern attacks on equality, social democracy, the welfare state, democratic institutions, and expertise. It is also necessary to contextualise conspiracy theories within the ecology and economics of digital media to understand the relationship between forms of mediation and content. Conspiracy theorising, albeit in different guises, is something of a historical constant. Historians have traced the use of rhetoric akin to conspiracy theorising back to Ancient Rome, for example (see (Pagán 2008). Nevertheless, conspiracy theory is shaped by the particular political, social, technological, and epistemological moment in which it arises. It sometimes reflects and sometimes refracts the anxieties and concerns of each era. Covid-19 conspiracy theories have appeared in many languages and in many parts of the globe, but as we are focusing on the Anglo-American context and on conspiracy theories in English, our observations will be focused accordingly. The purpose of this post is not to provide simple narratives of causation. Rather, we want to examine different historical forces that help to explain the rise of feelings of grievance, disaffection, and disenfranchisement and the links this may have to sympathy for populist movements and/or conspiracy explanations. (None of which is inevitable: grievance from at least some of the same factors described below has also been channelled into racial justice movements and protests, for example.)

Trust in Government, Institutions and Experts

Research demonstrates a general correlation between low levels of trust in government and a reliance on conspiracy thinking (see Smallpage et al. 2020, 273). This is important to note given that Pew Research has found a steady decline in trust in government in the US since it began polling about this issue in 1958. In that first year, 73% of Americans said that they can trust the government in Washington to do what is right “just about always” or “most of the time”. In 2019, that figure was just 17%. In a more finely-tuned analysis, the Edelman Trust Report looking at different developed countries has identified a growing “trust gap” between a more trustful informed elite and a distrustful mass population.

While dwindling trust in government has been evident for some time, it is now reinforced by populist politicians and leaders who wish to distinguish themselves from the political milieu, government bureaucracy, and expert advisors by aligning themselves with “the people”. Think of Trump’s promises to “drain the swamp”, Michael Gove’s claim that “people in this country have had enough of experts,” or Nigel Farage’s claim that the Brexit vote was a “victory for real people”. As well as denouncing professional politicians and government agencies, contemporary populist politicians promote a general anti-intellectual, anti-legacy media, anti-NGO, and anti-science stance until it is hard to see where trust should or could be placed. While trust, or at least loyalty, is placed in the very figure who questions the trustworthiness of other figures and institutions, populists like Trump might just be “different elites who try to grab power with the help of a collective fantasy of political purity” (Müller 2016). However, cynical mobilisations of distrust should not lead us to infer that all lack of trust in government is wrong-headed. Thinkers like Thomas Frank, Will Davies, and Michael Sandel all place the blame for anti-expertise populism at the door of liberals who have relied on a form of technocratic elitism that is sustained by the myth of meritocracy. (Frank, who carefully delineates the original populist movement as a multi-racial coalition of working people seeking economic democracy, calls Trump and others “faux populists”.) Declining trust might be understandable when we recognise the depth of what Frank calls “expert failure” in recent decades. He writes, “I refer not merely to the opioid crisis, the bank bailouts, and the failure to prosecute any bankers after their last fraud-frenzy; but also to disastrous trade agreements, stupid wars, and deindustrialization. . . basically, to the whole grand policy vision of the last few decades, as it has been imagined by a tiny clique of norm-worshipping D.C. professionals and think-tankers.”

The need for trust between the people and experts goes back to the beginnings of the American republic: “Ordinary people had to turn to some combination of elected officials and what would eventually be called ‘experts’ to supply, candidly and transparently, the preliminary factual truths that they needed to make well-reasoned judgments at the ballot box” (Rosenfeld 2018, 30). Democracy was never envisaged as a project that required voters to make arbitrary or baseless decisions in the dark. Rather, it acknowledged the necessity of translators, communication, outsourcing, and representation from the beginning. The system tolerates this tension between “the supposed wisdom of the crowd and the need for information to be vetted and evaluated by a learned elite of trusted experts” (30).

Some research shows that declining trust in experts seems to fall along partisan lines. Research by YouGov in the UK shows that supporters of the Conservative Party and UKIP, and those who voted to leave the European Union, are more likely to distrust experts from a range of professions. (It is also worth noting, given the sections on poverty and income inequality below, that the research also found that working-class people have less levels of trust than those in the middle-classes.) Matt Wood observes a similar trend with respect to partisanship in the US, “as conservatives became increasingly distrustful of scientists compared to liberals in the late-2000s, with campaigns like the March for Science serving only to further polarise views”.

The question of trust matters when it comes to conspiracy theories because a lack of faith in cultural, political, civic and scientific institutions and their representatives gives rise to scepticism about the evidence and information they put forth. Scepticism has been amplified by the epistemological relativism of the Trump administration and its talk of “alternative facts.” Indeed, the nature of evidence today is highly contested: people now question what counts as evidence, how it has been gathered, and how it can be used. Frank’s book on populism shows that early populist movements were keen for people to educate themselves and dig into economic data. Today, uncertainties about evidence per se encourages people to assemble their own rival archives of evidence from the deep recesses of the internet that exist beyond the verification performed by editors, academics and scientists. Indeed, such archives are valued precisely because they fall beyond the purview of such gatekeepers. In an era of information overload, it matters more what you feel has a ring of “truthiness”, as Stephen Colbert put it, rather than what experts have verified to be true. This is a sentiment exploited by right wing pundit Ben Shapiro who insists “facts don’t care about your feelings.” Effectively, as Jeremy Gilbert argues, people are pushed into the marketplace of ideas without the authoritative social institutions that could help with the need to make deliberative decisions.

As the work of Frank, Davies and Sandel indicates, we have to recognise that there may be good reasons why people lack trust in certain figures and institutions and the evidence they produce today. The question can then be reframed to ask whether institutions are trustworthy. While there are non-state as well as state institutions in play here, we want to focus in the next section on the latter to think about the ways in which the state has let people down.

Demise of the Welfare State

One convincing and simple explanation for distrust of the state and post-war conspiracy theories in America is that all kinds of conspiracies (including COINTELPRO, Watergate, Iran-Contra) were committed by government agencies throughout the twentieth century (see Olmsted 2009). Engaging in illegal or semi-legal covert activity is one way to lose the confidence of the public when such acts come to light. But we can also think about more quotidian and less newsworthy ways in which the state has betrayed the people.

In the UK and the US, notions of the scope of the state, of its role in wider society and the social good, have been systematically altered by the implementation of neoliberal policies since the 1970s. Margaret Thatcher famously remarked that “there is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women and there are families.” If society is the place where inequalities and injustices can be seen and potentially rectified by state intervention, neoliberals felt it was much better to obfuscate that visibility and instead promote the idea that each person alone is responsible for their financial success or failure. Gilbert suggests that the erosion of social welfare under these conditions has led to a deep disbelief in the possibility that public institutions could be supportive or even simply benign. In this case, he argues, the “deep state” that features in many conspiracy theories is simply “the state as such under neoliberalism.” In other words, while conspiracy theories fashion the deep state as an evil force undermining the will of the people, the neoliberal state is doing its dirty work in plain sight (deflecting responsibility for inequality, privatising public goods, implementing regressive taxation, producing forms of labour precarity, and deregulating capital). It would be a mistake to be too nostalgic about the actual welfare state. The state has never been a purely benign entity! Gilbert’s point, rather, is about how people think and feel about the state under conditions of late capitalism. He sees this disbelief that the state can be anything other than conspiratorial as inevitable once its function has shifted from that which might be able to protect you from the worst excesses of capitalism to that which will expose you to them.

The irony is that the very people who should lament the loss of state support are the ones who shout loudest about a sinister, omnipotent deep state. It is possible that the appeal of a deep state conspiracy theory like QAnon (that positions the head of state as battling the deep state) is that it provides a way out of such contradictions: it allows some forms of government interference to be experienced as good (“Send me my stimulus check personally signed by the president!”), while others are evidence of a vast Satanic deep state plot.

The demise of the welfare state certainly leaves citizens exposed to the excesses of capitalism. New global challenges in the 1970s such as stagflation and oil crises forced the UK’s Labour government to look for alternatives to Keynesianism. It experimented with forms of hybrid Keynesianism, but these measures failed to improve the UK’s financial situation. By the end of the 1970s, Britain was among the poorest of the OECD countries, having been ranked among the richest only twenty years before (Kus 2006, 506). The move away from Keynesianism and towards neoliberal policies was fully embraced by the Thatcher government of the 1980s as it implemented a monetarist approach to the economy, prioritising limits on inflation over full employment. Beyond the economy, Thatcher’s vision sought to alter the very relationship between citizens and state by firmly placing responsibility with citizens for their own welfare. The Conservatives justified welfare reform by claiming it would create incentives to work, produce self-sufficiency, and assure more personal freedom. Despite already ranking among the lowest European countries in terms of social security expenditure in relation to GDP in 1980, the Conservatives pushed through a series of budget cuts and reforms to the welfare state. For example, despite a 200% increase in the number of claimants of unemployment benefit between 1980 and 1987, spending on unemployment decreased by more than 50% over a period of 10 years (Kus 2006, 508).

The US picture is more complex because it never embraced a fully public welfare state, preferring a mixed model of private and public forms of security. This is why many US citizens’ healthcare insurance is provided by employers who then receive tax relief as an incentive. While less formalised, local welfare was on offer before federal level programmes, it is notable that the US introduced social insurance programs much later than most European countries. Whereas unemployment insurance, for example, was introduced in the UK in 1911, the US did not implement it until 1935. Equally, while the mixed public-private welfare model makes national comparisons complicated, the US lags behind welfare spending in most calculations.

As in the UK, it was the turn to neoliberalism (as both an economic and social project) that eroded welfare provision while at the same time casualising what forms of blue-collar labour hadn’t been off-shored within a globalised economy. Ronald Reagan implemented neoliberal monetary policies, tax cuts, deregulation and free trade and peddled the racist, inflammatory, stereotype of the “welfare queen”— typically depicted as an African American single mother living a glamourous life funded by the tax payer. But it wasn’t until Bill Clinton and his compromising strategy of triangulation in the face of a Republican ruled Congress that welfare was fully reformed along neoliberal lines. With Clinton’s approval, the Republicans implemented the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act. An integral part of this was the replacement of Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), created as part of the 1935 New Deal, with Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). TANF is a block-grant, the administration of which is devolved to states. Importantly, the value of the grant is fixed regardless of how many people are on the welfare rolls or how high the unemployment rate goes. Moreover, its value has been eroded over time by inflation.

Analysing data about TANF, the Centre on Budget and Policy Priorities reports:

TANF’s emphasis on taking benefits away when parents do not meet a work requirement has resulted in millions of families—most often those who face the greatest labor market challenges—losing access to the very benefits that could help them to escape deep poverty and improve their employment prospects. And Black and Latino children often live in the states where benefits are the lowest and the program serves the fewest families in poverty.

The financial crisis of 2007-8 created an additional 1.5 million families in poverty, placing strain on the already inadequate welfare programme. If we add to this the fact that because of increasing casualisation of the workforce in the US “the percentage of workers covered by health insurance and retirement benefits has decreased” in recent decades (Katz, n.d.), the welfare picture is bleak. This is important when considering conspiracy theories not only because of the many ways in which the state is failing citizens, creating possibilities for figurations of the state (and beneficiaries of the system) as conspiratorial, but because some research establishes a correlation between conspiracy thinking and low levels of income and education (Smallpage et al. 2020, 266). (Although we should be hesitant about overstating the connection given the high proportion of conspiracy beliefs across income brackets today (Smallpage et al. 2020).)

After four decades of living under a mode of rationality that minimises or denies the role of the state in social justice, rectifying inequality, or providing a safety net, and a decade of austerity in the UK, the key message of which was that the state cannot afford the level of investment in social care and services that people need, the financial and social packages offered as part of the response to the economic fall-out of the pandemic have been a revelation to many. It turns out that the state can provide support and care when required—such decisions have been revealed to be wholly political rather than common sense. Something similar became apparent in the US given the size of Obama’s post-crash stimulus package. Neoliberalism has always appealed to “common-sense”, insisting that “there is no alternative” to free markets, privatisation, and individualism, to borrow Thatcher’s slogan, even while simultaneously engaging in forms of intervention (what Robert Brenner calls “asset-price Keynesianism”) that prioritise corporate wellbeing over social welfare. As the state steps up during the Covid-19 pandemic, providing support payments (in the US) and covering the wages of those being furloughed (in the UK), some may feel confused about previous messages concerning the limitations and capacity of the state, or even suspicious.

When subjects are awarded full responsibility for their own survival under neoliberalism, the figure of the entrepreneur becomes key. This is the subject par excellence of neoliberalism. Michel Foucault writes, “the stake in all neo-liberal analysis is the replacement every time of homo œconomicus as a partner of exchange with homo œconomicus as entrepreneur of himself, being for himself his own capital, being for himself his own producer, being for himself the source of [his] earnings” (Foucault 2008, 226). This ‘rational actor’—this new and improved homo economicus—is able to thrive amongst the ruins of liberal democracy through modes of self-reinvention and self-exploitation. Sean O’Brien, a Research Assistant on this project, suggests we might think of the conspiracy theorist as a counterpart to the entrepreneur. If the entrepreneur is hyperrational, the conspiracy theorist is seen as hyperirrational. While the entrepreneur is identified with jujitsu moves up the ladder of opportunity, the conspiracy theorist is associated with downward class mobility and grievance. Both subjects seem to emerge out of precarity—job insecurity and increased exposure to risk—but one is a resilient go-getter, beating the system at its own game, while the other becomes paralysed within loops of paranoid logic and feels defeated or controlled by invisible forces. Both subjects also exude a kind of anti-state sensibility: the entrepreneur because s/he thrives in unregulated spaces of capital, the conspiracy theorist because s/he fears being thwarted by its machinations. What we increasingly see now, however, is a combination of the two figures as conspiracy entrepreneurs and influencers profit from conspiracist merchandise and broadcasting. The force of the entrepreneurial imperative of neoliberal capital extends to monetise even an apparent counterforce to it.

Income Inequality, the Financial Crash, and Austerity

We are describing the material conditions and ideologies that might make it less possible to consider the state as a supportive or benign entity and more possible to imagine it as susceptible to influence and operating with conspiratorial intent. Alongside the erosion of the welfare state, post-crash economic conditions might also have contributed to a sense that there are shadowy forces at work to exploit ordinary people.

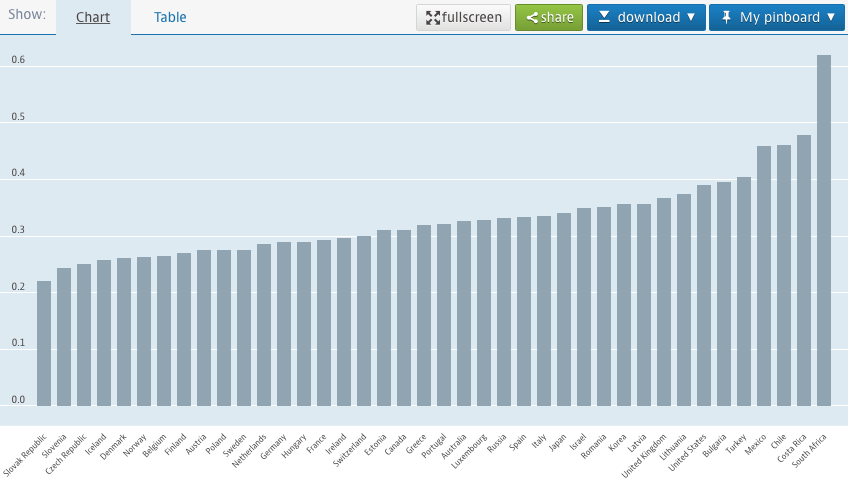

When we consider high levels of income inequality in the UK and US, it is easy to see why “elites” often become the target of conspiracy theorising. Since the 1980s, income inequality has remained high in the UK and has been steadily growing in the US. Both countries score highly on a sliding scale that uses the so-called Gini co-efficient. The Gini coefficient is used by some economists to compare, as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) explains, “the cumulative proportions of the population against cumulative proportions of income they receive. It ranges between 0 in the case of perfect equality and 1 in the case of perfect inequality” (2020).

Fig. 1: OECD data showing the Gini co-efficient of different countries

Fig. 2: Graph from The Guardian showing Britain’s rise in income inequality in the 1980s

In May 2019, The Guardian’s economics correspondent, Richard Partington, reported that pay for non-college-educated men in the US had not risen for five decades, while for the first time in 100 years, mortality for less-educated white men and women in middle age had led to a fall in the average life expectancy. Meanwhile, household incomes have increased faster for those in the top 5% than for those in the strata below since 1980, and between 1989 and 2016, the wealth gap between the richest and poorest families more than doubled. Such inequality falls along racial lines. In 2016, the median wealth of white households in the US ($171,000) was 10 times the median wealth of black households ($17,100). In the UK, the picture isn’t much better: “the richest 1% … have seen the share of household income they receive almost triple in the last four decades, rising from 3% in the 1970s to about 8%. Average chief executive pay at FTSE 100 firms has risen to 145 times that of the average worker, from 47 times as recently as 1998” (Partington 2019).

Crucially, the Covid-19 crisis has increased the wealth divide in the UK with BAME people hardest hit. 31% of UK households have lost a quarter of their income, while those in more secure lines of work have managed to save money by not going on holiday or eating out and those in the very highest earning brackets, with investments in the surprisingly buoyant stock market, have done well during the pandemic. In the US, according to researchers at the University of Chicago and the University of Notre Dame, the number of Americans living in poverty rose by approximately six million (a jump from 9.3% to 11.1%) between June 2020 and September 2020 while the wealth of tech billionaires like Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg soared. Bezos’s fortune has increased by $80 billion during the pandemic, for example. In addition, Wall Street investment banks like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley are turning a tidy profit (Morgan Stanley made a profit of $2.7 billion between July to September 2020, a rise of 25% compared to a year ago; and Goldman Sachs made a quarterly profit of $3.62 billion, almost twice the amount earned in the same quarter last year).

The UK and the US responded to the financial crash of 2007-8 in different ways. Like much of the European Union, the UK pursued a project of austerity, cutting the budget for public services, education and welfare with the intention of reducing the budget deficit, liquidating the structural deficit, and reducing the level of debt. The US implemented a more traditional path of Keynesian stimulus which enabled the US to regain its pre-crisis levels of GDP by 2011 (whereas the UK didn’t achieve this until 2014). But in terms of inequalities, the collapse of the housing market in 2008 meant that the property-dependent portfolios of middle class American households fell while the portfolios of the wealthiest, geared towards a quicky rebounding stock market, increased. Because the booming housing market had minimised the effect of wage stagnation, the collapse of the former arguably made the latter more apparent.

Robert Skidelsky argues that, “the effects of failing to take precautions against a big collapse of economic activity and the botched and inegalitarian recovery measures implemented by most governments from 2010 onwards have left a damaging legacy of political resentment. The electoral support for populist movements […] has deeper roots than mere economic distress. But the correlation between the collapse of 2008 and its consequences and the growth in support for populism is too striking to be ignored” (2018). While not all populist movements turn to conspiracy theories, many do and we can think of conspiracy theory itself as inherently populist in the way that it pits the people against the establishment (see Fenster 1999/2008, 84). If economic instability is one factor that allows populism to enter mainstream discourse and politics, it also shapes the conspiracy imagination.

Conspiracist Populism / Performative Authoritarianism

What is the relationship between conspiracy theory and populism? “Populism cannot be reduced to its typical content (anti-intellectualism, for example, or mass mobilization by a charismatic leader) or its typical effects (scapegoating or conspiracy theorizing)” because content and effects are historically contingent, writes Mark Fenster (2008, 85-6). He advises that we should think of populism more as a process that can be mobilised by the left or right (and sometimes tries to disrupt these categories altogether— think of Marine Le Pen’s comment in 2015, “Now the split isn’t between the left and the right but between the globalists and the patriots.”). Populism arises in democracies, according to Fenster, when the gap between the public and its elected representatives constitutes a crisis and “a movement can plausibly offer some more direct or ‘authentic’ means of representation in the name of the people” (86). If populism serves as a necessary possibility of representative democracy—suturing the wound of representation when the distance between the people and elected politicians becomes too wide—conspiracy theory “as a mode of populist logic,” is, therefore, “not foreign to democracy” (90). However, it has become increasingly clear in the twenty-first century that today’s version of populism and conspiracy theory alike “can play a destructive role by manipulating overly majoritarian, racist, or antidemocratic tendencies among the public” (90) and have played a part in undermining the ideals and institutions of liberal democracy.

Populist forces have been resurgent in Europe, the Nordic countries, South America, Asia, and the US. While all cases display regional variation and national specificity, many capitalise on feelings of disenfranchisement, insecurity about social status, fear of demographic and cultural change, and concerns about losing out to others. Populists deal in a Manichean world view pitching evil elites against the virtuous people. “The people” is a notion built on exclusions, of course; it does not include all of those who stand for values contrary to the populist’s vision. In Trumpist politics, for example, this included elites in general, but also scientists and other experts, legacy media, “woke snowflake Millennials,” “social justice warriors,” ethnic minorities, and undocumented immigrants. In this vein, during his presential campaign of 2015, Trump made the claim that “the only important thing is the unification of the people, because the other people don’t mean anything.” The populist’s conviction that they alone are “the expression of the one right and true majority” means that opposition is presented as “morally illegitimate” (Urbinati 2019, 120). This is important, Nadia Urbinati argues, because it lends itself to authoritarianism as “the leader feels authorized to act unilaterally” as they disavow pluralism and the concept of a legitimate opposition (120).

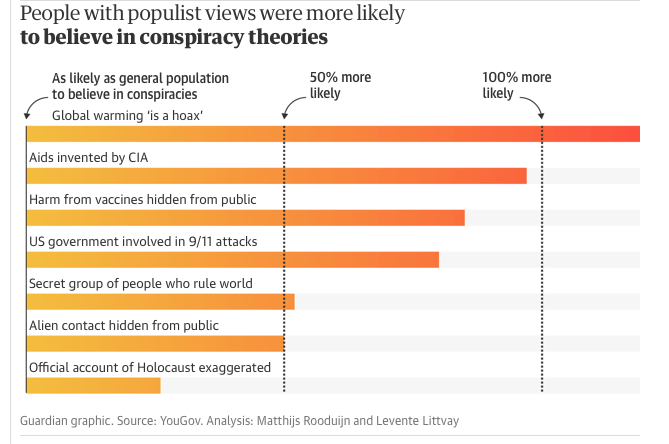

While populist rhetoric does not always slide into conspiracy theory, and some argue that “conspiracy theorists usually constitute a significant minority within populist movements” (Bergmann and Butter 2020), it’s clear that conspiracy theory is a discourse that populists draw on. Erikkur Bergmann and Michael Butter use the term “conspiracist populism” to indicate where and when the styles coincide. Some research approaches the issue slightly differently, claiming that people with populist views are more likely to believe in conspiracy theories.

Figure 3: From The Guardian

Benjamin Moffitt (2016) treats populism as a particular way of performing politics. This resonates with the kind of performative authoritarianism employed by Trump. After protesters against racial injustice were forcibly removed from Portland streets into unmarked vans by officers dressed and armed for combat in the summer of 2020, Anne Applebaum commented that unlike its twentieth century version, twenty-first century performative authoritarianism “does not require the creation of a total police state. Nor does it require complete control of information, or mass arrests. It can be carried out, instead, with a few media outlets and a few carefully targeted arrests.” Displays of power such as this were intended to bolster Trump’s hard stance on “law and order” during his re-election campaign.

We need to combine several of the terms in play here to understand the particular hue of Trumpist politics and the role conspiratorial narratives played in it. Perhaps he is best described as a conspiracist-populist who operated as a performative-authoritarian: a mode that encompasses rhetorical strategies and visual stunts.

In the UK, the campaign to leave the European Union was framed around the idea that the concerns of the EU government are remote from those of “real” British people. Again, we see populism given a foothold when the distance between the representatives and those that are represented is seen to be too wide. More than this, membership of the EU was configured as being a bad deal for the British people because the “Brussels bureaucrats” were actively working against the interests of British people (in a way that obscured the fact that elected British MEPs were part of that EU government). While the campaign for “Leave” was focused on amplifying concerns about immigration and lamenting a perceived lack of sovereignty, Nigel Farage, of UKIP, also employed explicitly conspiracist ideas. Indeed, he appeared many times on Alex Jones’ Infowars show, talking about “globalists” and a “new world order.” On these episodes, Farage repeated key conspiracy tropes: “Members of the annual Bilderberg gathering of political and business leaders were plotting a global government; the banking and political systems are working ‘hand in glove’ in an attempt to disband nation states; ‘Globalists’ are trying to engineer a world war as a means to introduce a worldwide government” and that “Climate change is a ‘scam’ intended to push forward this transnational government.”

It is important to note that populism has also been mobilised on the left. More than this, Frank reminds us that the original populist party challenged the precepts of capitalism. However, Daniel Denvir argues that because the more recent leftist movements often labelled populist do not claim to exclusively represent the one authentic people, the label is unjustified. In this light, Denvir continues, Bernie Sanders, Jeremy Corbyn, Syriza and Podemos might be better described as “plausible attempts to reinvent social democracy.” Frank, too, balks at the false equivalences that commentators drew between Sanders and Trump during 2016—how the accusation of populism became a dirty word. It is true, however, that leftist movements like Occupy, and its demonising rhetoric about “greedy bankers” and “corrupt politicians” fed into a populist narrative that has been subsequently exploited by forces of the right.

During the pandemic, a turn to what Gideon Lasco and Nicole Curato (2019) call “medical populism” is evident. They describe medical populism as “a political style based on performances of public health crises that pit ‘the people’ against ‘the establishment.’ While some health emergencies lead to technocratic responses that soothe anxieties of a panicked public, medical populism thrives by politicising, simplifying, and spectacularising complex public health issues” (1). While Lasco and Curato do not discuss conspiracy theories, we know how contemporary populism draws sustenance from, and turns towards, conspiracy thinking and their term offers a useful way to understand the dangers of populist and conspiracist framings of medical emergencies.

Ethno-Nationalism

While the original populist movement might have been multi-racial, today right-wing populist forces have licenced forms of ethno-nationalism. Ethno-nationalism is an ideology that propagates and capitalises on myths of a homogenous culture and a common history. It seeks to protect an imagined community or cultural identity from dilution by other, seemingly incompatible, imagined communities or cultural identities. Ethnonationalism shapes policies as well as rhetoric: borders might be securitised, immigration policy tightened, and political or economic sovereignty might be enacted through a retreat from regional coalitions or international organisations and commitments.

Ethno-nationalism is stoked by a feeling of what Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin call relative deprivation: “a sense that the wider group, whether white Americans or native Brits, is being left behind relative to others in society, while culturally liberal politicians, media and celebrities devote far more attention and status to immigrants, ethnic minorities and other newcomers” (2018). To illustrate this, they point out that 90 per cent of Trump’s core supporters believed that “discrimination against whites is a major problem in America.” And in the UK, 76 per cent of Brexit supporters felt things had “got a lot worse for me compared to other people” (Eatwell and Goodwin 2018). Ethno-nationalism offers ethnically white communities a way of appropriating the language of discrimination by “obscuring power differentials by putting whiteness or European descent at the same level as minority identities” (Gambetti 2018). In these scenarios, people eschew establishment politicians and policies, seeing them as having been unable to prevent the perceived relative deprivation by giving up national sovereignty too easily and giving in to elitist ideals of multiculturalism.

Rather than focus on the way that globalised open markets have resulted in investment moving south and east to find cheap labour, right wing populism capitalises on a fear of change in the dominant ethnic make-up of an area, of one culture being displaced by another. In some cases, this gets expressed in familiar conspiracist language. Consider Islamophobic conspiracy theories like “the great replacement theory”. This phrase originated in France but has been adapted by figures elsewhere (including reactionary right broadcasters like Canadian Youtuber Lauren Southern and the New Zealand Christchurch killer in his manifesto). It warns of an explicit plot to displace historically ethnically white and Christian cultures through the influx of a different ethnicity, race or religion. Hari Kunzro explains how the idea has run its course through the right-wing media ecosystem and beyond: it “has made its way from the salons of the French far right into the chans, and out again to Fox News, informing the Trump administration’s staging of the so-called border crisis (a term that is often enough repeated uncritically even by members of the so-called fake news media).”

Culture Wars and Polarisation

States have long asked self-reflexive questions about national identity and values. Such questions can only be termed “culture wars” when there is little to no consensus about the answers—when disagreements are considered existential threats and become cause for deep grievance. Culture wars can be read as the transfiguration or displacement of purely economic and political issues. For example, by this explanation structural accounts of poverty are obscured by cultural narratives that distinguish between the “deserving” and “undeserving poor” (as the already mentioned “Welfare Queen” stereotype in the US, or the Daily Mail’s bid to catch benefit fraudsters in the UK attest to). However, this approach risks dismissing cultural concerns—disregarding them as false consciousness—when it’s clear from the Brexit vote and working-class support of Trump that culture or values are often far more important than socio-economic status to many people. Working-class people might not, in any simple fashion, be “voting against their interests” if, as Alan Finlayson argues, “interests are multiple, material and ideal, and often contradictory.” Rather than positioning culture as a displacement, it might just be that terrain on which politics is fought (a proposition that undergirds the scholarly discipline of cultural studies).

As a social as well as economic programme, the neoliberalism embraced by Reagan in the 1980s also shaped cultural attitudes and the scope of debates concerning them. One of neoliberalism’s original architects, Fredrich Hayek, emphasised the role of a traditional moral order that no state should interfere with. State imposed social justice, in Hayek’s view, has no place—it is merely the imposition of an artificial order that erroneously configures the state, rather than the individual, as the responsible unit. This means that redistributive interventions as well as what Hayek called the “social justice warrior,” a pejorative term that has been picked up by the right today, can then be presented as unwelcome interruptions to a common-sense, natural order—as infringements on freedom (see Brown 2019).

In 1992, Pat Buchanan talked about “a war for the soul of America.” He claimed that the election that year was about “whether the Judeo-Christian values and beliefs upon which this nation was built” would endure (quoted in Hartman 2019, 1). In the 1980s and 1990s, the culture wars focused on “abortion, affirmative action, art, censorship, evolution, family values, feminism, homosexuality, intelligence testing, media, multiculturalism, national history standards, pornography, school prayer, sex education, the Western canon” (Hartman 2019, 1). Some of these issues are still highly contested, albeit in slightly different manifestations. To update this list for the contemporary moment, we would need to remove some and add trans rights; climate change; gun ownership; undocumented immigrants; statuary of slave owners and other monuments; what constitutes sexual harassment; and now, also, responses to the pandemic, often centring on mask wearing and attitudes towards vaccination.

In the UK, the turn to Thatcherism instigated a war on “the loony left”, which included unions, Ken Livingstone’s left-wing Greater London Council, CND, and movements for equal rights. The British culture wars of the 1980s were shot through with the right’s attempts to validate a traditional, monocultural morality (for example through the implementation of the homophobic Clause 28), leveraging patriotism (through the Falklands War), and limiting definitions of British identity (by, for example, either doing nothing to tackle or actively supporting institutional racism, which led to events such as the Day of Action organised because of institutional failures concerning a fire in New Cross in which a number of black teens perished and the uprisings in Brixton against police brutality, both in 1981).

The cultural-political landscape in the twenty-first century shifted thanks to a series of liberal social reforms. During the Labour government of 1997-2010, it became far less acceptable to express racism and homophobia in public. Today’s culture wars in the UK, however, offer prejudice new avenues for expression, focused as they are on immigration, Brexit, trans rights, and the relationship of Britain to its history of Empire and/or slavery. Denigrations of the “loony left”, reinvented as an attack on “wokeness”, focus on “political correctness,” the funding of the BBC, the role and value of universities, and the school curriculum. Given that ideology presents the cultural as natural, the politically motivated as self-evident, it is wholly fitting that a self-appointed group of Conservative MPs have called themselves the “Common Sense Group”. In the wake of Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020, the group complained about museums that are reconsidering the legacy of historical figures and lobbied for tougher immigration policies.

Only an acutely ahistorical view could claim that the US is more polarised than ever before given how divided the nation was during its civil war. With regards to the UK, some research suggests that a vociferous minority on social media make it seem more divided than in fact it is. However, as the finely balanced and hotly contested recent election in the US displays, as well as the tight Brexit referendum in the UK, polarisation rather than consensus politics seems to be a lived reality in ways that have intensified in recent history. Moreover, polarisation is today amplified by asymmetric media structures, partisan media outlets, and social media in such a way that it is clear that the tenor of debates rule out compromise or consensus. The other side is depicted not as mistaken, but as stupid and even evil. Polarised, entrenched positions can push some further to the extremes of political belief. This is important when studying conspiracy theories because in comparison to moderates, extremists have been found to be more prone to conspiracy thinking (e.g. van Prooijen et al. 2015; Krouwel et al. 2017).

The “alt-right” has amplified the culture wars by disparaging and goading its perceived enemies, calling refugees “rapefugees”, ridiculing “social justice warriors” and even moderate conservatives which they name “cuckservatives” (see Dafaure 2020). Particular vitriol is reserved for women within online subcultures like incels (self-identified involuntary celibate men who feel excluded by women from the sexual economy). They accuse progressives of “cultural Marxism”—of curtailing individual freedoms through aggressive forms of identity politics and plotting to destroy traditional ways of life and Western culture. Such attacks clearly respond to challenges to white privilege, patriarchy, and racial capitalism. Such sentiments did not remain on the fringes: Kunzru notes, “Along with Reddit’s r/The_Donald, 8chan and /pol/ became major drivers of far-right content into the mainstream media.” In addition, Trump’s loose alliance with figures of the alt-right and his refusal to condemn far right protesters also helped extreme ideas enter mainstream discourse and visibility.

Both the image boards of the deep vernacular web and social media from the surface web on which these far-right sentiments are aired are ill-suited to building consensus. The expression of far-right ideas is defended through an appropriation of the language of personal freedoms. This is where conspiracy theories come in, as they become a limit test for free speech in the current climate. When is a conspiracy theory about George Soros anti-Semitic hate speech? When does the right to express a conspiracy theory regarding mask wearing or vaccine taking impinge on another’s right to good health or even life? Is belief that Tom Hanks, as part of the cosmopolitan elite, is buying and ingesting adrenochrome harvested from children a cultural expression of difference or a libellous accusation?

Conspiracy theories such as QAnon offer post-truth manifestations of the culture wars. They are offered as if to engage in a debate, but because they eschew consensus reality, there is not the necessary shared ground to begin an exchange. In this sense, conspiracy theories that purport that the Holocaust is a Jewish fabrication or that climate change is a hoax orchestrated by the liberal elite, cannot and perhaps should not be debated in the real sense of that term. (This does not mean that such propositions should not be researched as cultural phenomena, but that they should not be framed as one half of a two-sided debate on a public platform.) “Debate” suggests that there are two legitimate interpretations of the same historical or scientific facts (just as the “war” of “culture wars” suggests a battle between forces using similar tactics and weapons). Bad faith arguments based on false equivalences get cynically defended as relativism: as simply what someone happens to believe. Do all beliefs have a place in the public sphere? Just as culture wars seem to entrench positions, there can be no reconciliation or agreement at the level of logic and epistemology between many conspiracy theories today and those that debunk them. To do so would require one side to completely acquiesce to the other side’s world view. This is, of course, how many feel about culture wars, which is why social media is so rife with practices of and incitements to “cancel” or “deplatform” those that people disagree with. For conspiracy theorists and peddlers of fake news, the platforms themselves have started to deplatform during the pandemic—a move which inevitably stokes the conspiracist flames further, interpreted as it is as censorship and suppression.

Intensified Disinformation Campaigns

While most conspiracy theories we come across on social media and closed messaging groups are circulated by free actors, there is also a vast amount of state sponsored disinformation to contend with. Authoritarian states such as Russia, China, Turkey and Iran have been found to produce and/or amplify fake news or disinformation. Disinformation has taken over from Cold War era propaganda. Whereas propaganda was intent on persuasion and ideological conversion, disinformation seems designed to confuse and disorient. Think, for example, of Russian interference in the lead up to the 2016 presidential campaign. Thanks to the Mueller investigation, we know that Russian troll farms developed a sophisticated network of social media accounts and groups designed to look like home grown content. The Russian campaign suppressed support for Hillary Clinton and hardened Trump’s base through conspiracist narratives and false claims. Such tactics have become especially concerning during the Covid-19 crisis. In October 2020, The Times uncovered a Russian fake news campaign to cast doubt on the safety of the Oxford vaccine trials and reported a month later that GCHQ had begun an offensive cyber-operation to counteract anti-vaccination disinformation being spread by hostile states.

Lest we think the phenomenon confined to authoritarian states, it’s clear that forms of disinformation are also produced by politicians in liberal democracies. Trump’s reliance on disinformation, most dangerously during the pandemic, offers too many examples to mention. The UK’s Conservative government might be engaging in a scientifically robust public information campaign during the pandemic, but they have also previously engaged in disinformation tactics. For example, during a televised debate between Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn during the 2019 election, the Conservative Party Twitter account changed its name to @FactcheckUK as it rebutted Corbyn’s statements.

What this means is that the information ecosystem becomes increasingly confused and confusing, arguably causing people to retreat into factions, guided simply by which narrative appeals most or confirms their world view. This reduces the chance of corrective, scientifically robust information reaching those who might benefit from it most, whether in the middle of a pandemic or not.

Surveillance Capitalism

One final contextual factor we will introduce here is what Shoshana Zuboff (2019) has called “surveillance capitalism” (although given the way data harms disproportionately affect marginalised communities, “surveillance racial capitalism” might be more accurate). She uses this term to identify an important turning point when data extraction for system and service optimisation gave way to selling data surplus to third parties. She explains that Google began by putting behavioral data “to work entirely on the user’s behalf” (69), but that pressure following the dot-com bubble caused it to transform this surplus into revenue. The exact nature of this exploitation is “the rendering of our lives as behavioral data for the sake of others’ improved control of us” (94). Ultimately, Zuboff warns readers of the unprecedented and asymmetric power yielded by data capitalists. Surveillance capitalism is now a ubiquitous business model for platforms.

This technological and economic paradigm is important for our research project because it means that conspiracy theories shared online are not only profitable for conspiracy entrepreneurs (those people who produce conspiracy content and merchandise), but digital platforms also. It’s true that social media platforms have developed policies about Covid-19 misinformation and have sought to deplatform particular purveyors of conspiracy content. However, their business models require a certain amount of content agnosticism particularly in stages of consolidation (which is why newer platforms like Gab and Parler have no such policies—Gab-founder, Andrew Torba, actually welcomed QAnon). It doesn’t matter to Mark Zuckerberg, for example, if Facebook users are posting about cats or conspiracies as long as they engage with the platform and enable Facebook to collect their data. Linking, liking, and sharing are all important when attention (and the personal data that attention yields) is at a premium. Some scholars and non-profits, like the Global Disinformation Index, believe that the current infodemic can be combatted by rendering fake news and misinformation unprofitable. This is no small feat. It involves challenging the very models of surveillance capitalism and internet advertising upon which digital platforms depend.

We might also want to take into consideration the complex information ecology that allows more fringe ideas to feed the mainstream platforms that are based on this data-harvesting business model. Marc Tuters, a key member of our research team, has written about the flow of ideas between the deep vernacular web and mainstream social media. The former, he argues, is characterised by masks, the anti- and impersonal, the ephemeral and aleatory, the collective, and remains stranger-based whereas the latter is based around faces, the personal, the persistent and predictable, the individual, and friend-oriented (de Zeeuw and Tuters, 2020). Despite radically different cultural codes, relations, experiences, and business models (the deep vernacular web does not rely on advertising revenue or data harvesting), ideas including conspiracy theories often emerge within the deep vernacular web and migrate to other platforms, shedding their original context and (often ironic) inflection. The anonymity upon which image boards like 4Chan and 8kun work facilitates the production of baseless theories that can then migrate—sometimes in diluted form, sometimes strengthened by “research” through links to other conspiracist web content—to spaces that require identification. As such ideas enter the monetised and monetisable spaces of the surface web, a cult of celebrity (for figures like Alex Jones or David Icke, for example) overtakes the allure of anonymity.

The contexts included here are not exhaustive by any means and we will be drawing on others in future posts. Equally, these brief accounts necessarily simplify a complex story. Nevertheless, in articulating them together near the beginning of the project, we hope to emphasise the importance of thinking contextually and historically for understanding conspiracy theories as a form of knowledge, a mode of politics, and a symptom of cultural anxiety. Conspiracy theories must be understood as political, cultural and epistemological entities; as having both a long history and contemporary specificity; and as shaped by the dominant mode of communication of each era.

References

Bergmann, Eirikur (2018) Conspiracy and Populism: The Politics of Misinformation. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Bergmann, Eirikur and Butter, Michael (2020) “Conspiracy Theory and Populism.” The Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theory. London and New York: Routledge.

Brown, Wendy (2019) In the Ruins of Neoliberalism: The Rise of Antidemocratic Politics in the West. New York: Columbia University Press.

Crewe, Tom (2016) “The Strange Death of Municipal England.” The London Review of Books 38 (24). December. https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v38/n24/tom-crewe/the-strange-death-of-municipal-england

Dafaure, Maxime (2020) “The ‘Great Meme War’: The Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies.” Angles: New Perspectives on the Anglophone World 10. https://journals.openedition.org/angles/369

Eatwell, Roger and Matthew Goodwin (2018) National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy. London: Penguin.

Fenster, Mark (1999/2008) Conspiracy Theories: Secrecy and Power in American Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Foucault, Michel (2008) The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978-79. Translated by G. Burchell. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gambetti, Zeynep. “How ‘alternative’ is the Alt-Right?” Critique and Praxis 13/13, 10 November 2018. http://blogs.law.columbia.edu/praxis1313/zeynep-gambetti-how-alternative-is-the-alt-right/

Hartman, Andrew (2019) A War for the Soul of America: A History of the Culture Wars. Second Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Katz, Michael B. (n.d.) “The American Welfare State.” History in Focus. https://archives.history.ac.uk/history-in-focus/welfare/articles/katzm.html

Krouwel, Andre, Yodan Kutiyski, Jan-Willem van Prooijen, Johan Martinsson, and Elias Markstedt (2017) “Does extreme political ideology predict conspiracy beliefs, economic evaluations and political trust?” Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 5(2): 435–62.

Kus, Basuk (2006) “Neoliberalism, Institutional Change and the Welfare State: The Case of Britain and France.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 47 (6): 488-525.

Lasco, Gideon and Nicole Curato (2019) “Medical Populism.” Social Science and Medicine 221: 1-8.

Moffitt, Benjamin. (2016) The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation, Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Müller, Jan-Werner (2016) “Trump, Erdoğan, Farage: The Attractions of Populism for Politicians, the Dangers for Democracy.” The Guardian. 2 September. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/sep/02/trump-erdogan-farage-the-attractions-of-populism-for-politicians-the-dangers-for-democracy

OECD (2020), Income Inequality (indicator). doi: 10.1787/459aa7f1-en

Olmsted, Kathryn (2009) Real Enemies: Conspiracy Theories and American Democracy, World War I to 9/11. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pagán, Victoria E. (2008) “Toward a Model of Conspiracy Theory for Ancient Rome.” New German Critique 103: pp. 27–49.

Partington, Richard (2019) “Britain Risks Heading to US Levels of Inequality, Warns Top Economist.” The Guardian. 14 May. https://www.theguardian.com/inequality/2019/may/14/britain-risks-heading-to-us-levels-of-inequality-warns-top-economist

Rosenfeld, Sophia (2018) Democracy and Truth: A Short History. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Skidelsky, Robert (2018) “Ten Years on from the Financial Crash, We Need to Get Ready for Another One.” The Guardian. 12 September. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/sep/12/crash-2008-financial-crisis-austerity-inequality

Smallpage, Steven M, Hugo Drochon, Joseph E. Uscinski and Casey Klofstad (2020) “Who Are the Conspiracy Theorists?” Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories edited by Michael Butter and Peter Knight, 263-277. London and New York: Routledge.

Urbinati, Nadia (2019) “Political Theory of Populism.” Annual Review of Political Science 22: 111-127. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050317-070753

Van Prooijen, Jan-Willem, Andre P.M. Krouwel, and Thomas V. Pollet (2015) “Political Extremism Predicts Belief in Conspiracy Theories.” Social Psychological and Personality Science 6(5): 570–8.

Zuboff, Shoshana (2019) The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. London: Profile.

This post is published under the terms of the Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) licence.